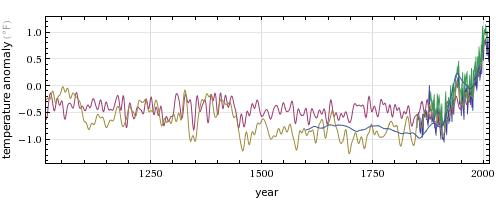

Figure 1

Temperature Anomalies during the Past 1000 Years

Source: Wolfram Alpha

“Well, who you gonna believe, me or your own eyes?” Despite their seeming familiarity, these words aren’t an absurdist argument posed by a climate change denier. These words spoken by a disguised Chicolini in the bedroom scene from Duck Soup, however, do present a type of argument that works—but only for a very specific, receptive audience.

Yet, evidence to the contrary is overwhelming. “Warming of the climate system is unequivocal, as is now evident from observations of increases in global average air and ocean temperatures, widespread melting of snow and ice and rising global average sea level.” Graphics like those displayed in Figure 1 provide compelling examples of evidence in support of the global warming associated with climate change.

Despite this solid science, heated opposition to the idea of climate change, in particular, anthropogenic global warming, has persisted since the idea widely entered the public conscience after NASA’s Dr. James Hansen’s testimony to Congress in 1988. Why does lack of belief in climate change endure? Are there problems with the science? Or, is there a failure in climate science communication?

The persistence of a lack of belief in climate change is almost certainly not due to problems with the science. Climate change is a scientific theory that has withstood the tests of repeated experiments and observations. Like all theories, climate change is built upon hypotheses that are repeatedly tested using the scientific method. As with all theories, climate change is falsifiable, and, if and when it is falsified, it must be replaced by a new, falsifiable theory which incorporates the new evidence.

Whether or not there is a failure in climate science communication is more problematic. It can certainly be argued that, at various levels, the press has failed to communicate effectively about aspects of climate change that are important to understand in order to pique the curiosity of its audience. The extent of scientific consensus, the magnitudes of the extents of global warming and its probable consequences, the social and distributive aspects of justice with respect to externalities, and the potential for actions driven by perverse incentives could be better explored as aspects worthy of public discourse. In this manner, public discourse in addition to scientific method can become an aspect of policy argument.

One method of explaining the failure of climate science communication to influence climate change acceptance is to look at the process of climate change acceptance as consisting of factors whose discrete levels of acceptance can, to a large degree, be independent. For example, these factors might include:

- Level of acceptance of the scientific validity of climate change (scientific reality). If considered on a standard Likert scale where a score of “5” indicates strong agreement, a climate change believer might score a 5. Someone who is undecided on the issue might score a 3; and a climate change denier, 1.

- Level of acceptance of the potential for catastrophic consequences associated with climate change (consequences). On a Likert scale a climate change believer might score a 5. Someone who is undecided on the issue might score a 3; and a climate change denier, 1.

- Level of acceptance of the potential for man-made mitigations which can nullify the catastrophic consequences associated with climate change (mitigations). On a Likert scale a climate change believer might score a 5. Someone who is undecided on the issue might score a 3; and a climate change denier, 1.

- Level of acceptance of the tenets of one’s predominant influence group with respect to influence on climate change acceptance (acceptable tenets). On a Likert scale a climate change believer might score a 5. Someone who is undecided on the issue might score a 3; and a climate change denier, 1.

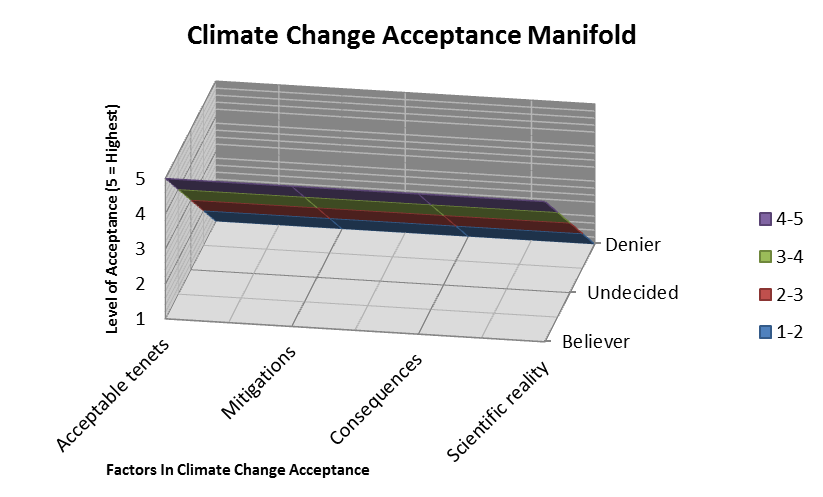

Figure 2 displays a two-dimensional manifold of the levels of acceptance of the climate change acceptance decision factors for the examples of believers, undecideds, and deniers outlined above. The average acceptance score for believers is 5 (“strongly agree” about climate change); for the undecided, 3 (“undecided” about climate change); and, for deniers, 1 (“strongly disagree” about climate change).

Figure 2

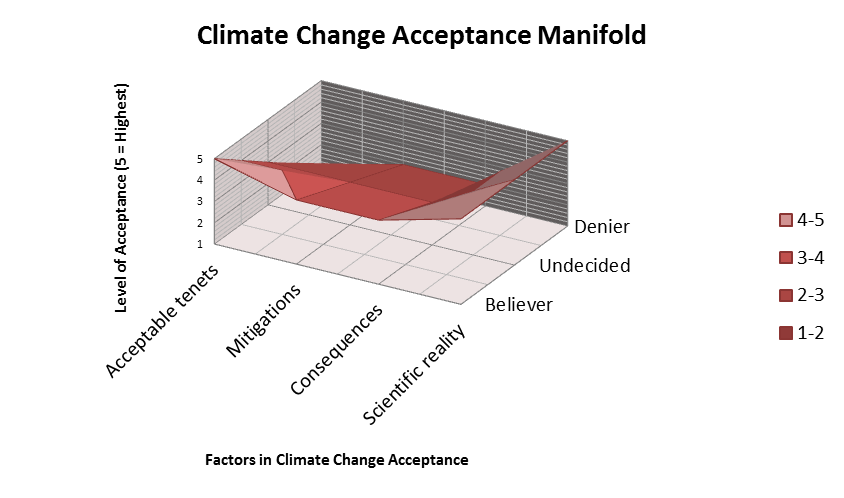

Figure 3 repeats Figure 2 with a few data changes. In this example, these factors include:

- Level of acceptance of the scientific validity of climate change (scientific reality). If considered on a standard Likert scale where a score of “5” indicates strong agreement, all three groups by level of overall belief score a 5.

- Level of acceptance of the potential for catastrophic consequences associated with climate change (consequences). On a Likert scale a climate change believer might score a 4. Someone who is undecided on the issue might score a 3; and a climate change denier, 2.

- Level of acceptance of the potential for man-made mitigations that can nullify the catastrophic consequences associated with climate change (mitigations). On a Likert scale a climate change believer might score a 4. Someone who is undecided on the issue might score a 3; and a climate change denier, 2.

- Level of acceptance of the tenets of one’s predominant influence group with respect to influence on climate change acceptance (acceptable tenets). On a Likert scale a climate change believer might score a 5. Someone who is undecided on the issue might score a 3; and a climate change denier, 1.

If these scores are used and each factor is weighted equally, a climate change believer scores a 4.5. Someone who is undecided on the issue scores a 3.5; and a climate change denier, 2.5. Assuming an average score of 3 implies indifference, one can be a climate change denier despite strong acceptance of the scientific validity of climate change. The influence of one’s socioeconomic peers on one’s overall level of acceptance is significant.

Indeed, if each factor is weighted differently—for example, 70% is weighted on acceptable tenets, and 10% each is weighted on scientific reality, consequences, and mitigations—the effects are more pronounced. Here, a climate change believer scores a 4.8. Someone who is undecided on the issue scores a 3.2; and a climate change denier, 1.6. In this case, the overall scores are close to the Figure 1 scores despite uniform scores by belief group with respect to scientific reality.

Figure 3

How, then, if the acceptance of the tenets of one’s predominant influence group with respect to influence on climate change acceptance is the predominant cause of the lack of climate change acceptance (or more simply, if institutional peer pressure dominates climate change acceptance), do we approach influencing climate change acceptance from a climate science communication perspective? First, we need to recognize that concentration on short-term, self-interested goals, the existence of asymmetries between winners and losers, focus on amoral objectives, and lack of effective regulation of perverse incentives are present in many similar scenarios (e.g., EMF effects in wireless communications, environmental impacts of hydraulic fracturing in the natural gas industry, siting decisions in hazardous infrastructure, off-shore oil exploration/extraction and the petrochemical industry). Accordingly, lessening the impact of institutional peer pressure becomes a general communication challenge.