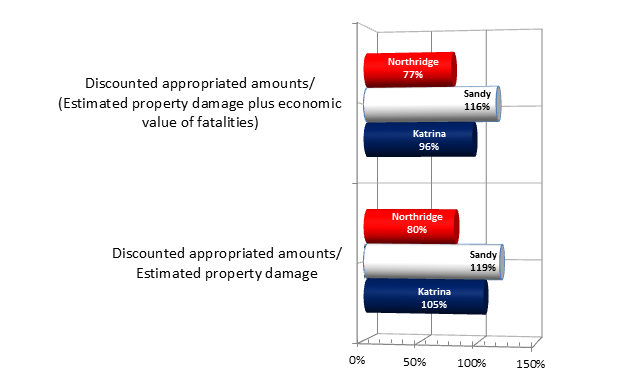

Federal Disaster Relief as a Percentage of Disaster Losses:

Hurricane Sandy, Hurricane Katrina, and the Northridge Earthquake

The blustery grandiloquence of Gov. Chris Christie (R-NJ) demanding passage of federal Hurricane Sandy relief funding in the weeks before Congress approved its second and more significant portion of Sandy aid funding on January 29, 2013 was—to a degree largely unrecognized—an exercise in the rhetoric of greed. Of course, one may argue that being greedy on behalf of one’s constituents is both admirable and as American as the Jersey Shore. However, when the money you’re fighting for comes from all Americans, your constituency is the American taxpayer—not only the voters of New Jersey.

After any disaster anywhere in America, our federal government should have an open checkbook “properly understood” that covers appropriate costs as they’re incurred. Immediate funding of rescue missions, of relief efforts, and of the initial recovery for those injured or left homeless or without jobs should be priorities. After a reasonable rescue and relief period, however, the federal government should prioritize continued rebuilding and mitigation efforts, identify bad practices, attach conditions on payments to lower levels of government, the private sector, and individuals based on conformance to acceptable practices, and demand strict, continuing accountability and transparency. Passing a bill which allocates an astronomically large sum to support an unknown quantity of work before we know what work needs to be done, what portion of this work can be funded within our rules and regulations, and how these acceptable tasks and funds shall be properly accounted works against these ends. Simply put, it is irresponsible.[1]

Let’s examine more closely the federal monetary response to the two most recent U.S. mega-disasters, Hurricane Katrina and Hurricane Sandy, and to Southern California’s own Northridge Earthquake of 1994. Hurricane Katrina was a whopper—over $108 billion in U.S. property damages, at least 1836 U.S. fatalities, and untold and continuing suffering. To date, federal aid appropriated on behalf of Hurricane Katrina relief has been approximately $114 billion.

Hurricane Sandy is another massive disaster. U.S. property damages related to the storm and its flooding will probably top $50 billion, there have been at least 132 U.S. deaths, and millions have suffered. To date, total federal aid appropriated on behalf of Hurricane Sandy relief has been approximately $60.2 billion.[2]

The Northridge quake was also devastating, with over $20 billion in property damages (in 1994 dollars) and 57 fatalities. Federal aid appropriated on behalf of Northridge Earthquake relief was approximately $16 billion (in 1994 dollars).

Depending on how one calculates the costs of these disasters, federal aid as a percentage of the disaster losses ranges from about 96 percent to 105 percent for Hurricane Katrina, from about 116 percent to 119 percent for Hurricane Sandy, and from about 77 percent to 80 percent for the Northridge Earthquake. After including discounts in each disaster’s net funding due to the delays in getting money appropriated (for Katrina, the average number of days until an appropriation was 12 days; for Sandy, 88 days; and, for Northridge, 36 days), all of these percentages change by less than one percent. The question is obvious. What accounts for the fact that, on a dollar-for-dollar loss basis, Sandy victims can expect to receive somewhere between $1.13 and $1.22 for every dollar that Katrina victims received and $1.50 for every dollar that Northridge victims received? Is there pork in Sandy relief, were Northridge and Katrina victims short-changed, did Katrina set a new baseline for federal disaster relief of mega-disasters (and the difference an indiscriminate mix of inflation and noise), or is there another explanation?

As with the answers to many complex questions, the answer is probably, “All of the above.” Consider the pork barrel aspect of disaster relief. What constitutes a disaster loss subject to federal aid is often a matter of opinion:

- For example, should private dwellings, businesses, and public entities be required to maintain property insurance covering disaster perils? If so, how much should they be required to spend in premiums as a percentage of coverage (or a percentage of their covered resource) in order to be considered insured such that their uninsured or underinsured losses should be back-stopped by federal assistance? What about insurance coverage for perils that are subject to limited commercial availability and plagued by affordability issues—namely, flood, named storms, and earthquakes?

- Should private dwellings, businesses, and public entities be given federal relief assistance for losses incurred in high-risk flood zones? If so, should this be limited to National Flood Insurance Program limits? Should structures with repeated disaster assistance claims be limited with respect to certain numbers or amounts of disaster claims?

- For Public Assistance program disaster relief claims, should repair and replacement of infrastructure be on a depreciated value basis? Also, if infrastructure were inadequately protected before a disaster, should disaster claim settlements be reduced as a penalty to the offending public entity?

- For mitigation-related work as part of public assistance disaster claims, should this work be funded only on a pro rata basis (with local public entities participating)? And mitigations such as repeatedly replenishing the sand on storm-ravaged beaches should be recognized for what they are—exercises in futility.

One thing is certain. Federal disaster relief policy needs reform. At a minimum, the amount of Sandy disaster relief funding may indicate that lessons from Katrina mismanagement have not been learned. The federal government needs to articulate FEMA’s purposes and funding guidelines more clearly. Damage to publicly-owned property that is directly attributable to a disaster and that was either uninsurable or underinsured (but, in the case of local governments, not at the fault of the local agency) should be covered fully by the federal backstop. Depreciation, lack of proper maintenance, intentional under-insurance, and other “cost saving” tricks by local agencies should be deducted in the adjustment of claims. Risk-based appropriations’ algorithms that include the disaster zone’s fiscal capacity to respond to the disaster on its own and updated FEMA per capita indicators (perhaps, measured by a weighting on Congressional district and state) should supplant the current ad hoc appropriations’ process.

The federal government also needs to collect demographic data on disaster relief applicants (perhaps at the point of award or first denial of an application rather than at the time of application) in order to verify that disaster victims in poorer, more heavily minority areas aren’t also the victims of racism and economic classism.

The continuing threats of rising inequality, ill-conceived settlement patterns and forms, and the negative consequences of climate change will only serve to exacerbate problems in future disaster relief activities. An era of increasing numbers and severities of disasters coupled with relief actions which may appear to reflect the Orwellian notion that “some … are more equal than others” doesn’t bode well.

“The greatness of America lies not in being more enlightened than any other nation, but rather in her ability to repair her faults,” wrote Tocqueville in Democracy in America. Disasters and the ways we respond to disasters, like mirrors, swiftly and accurately reveal our warts and blemishes. Consistency in how we assess and respond to disasters would be a major step toward achieving social justice within America.

[1] But, of course, you could argue that appropriations are not necessarily firm commitments. Technically, some or all of an appropriation could be rescinded.

[2] Losses from economic disruption and aid in the form of tax credits have been ignored for these two disasters for purposes of this comparison because, while the Sandy economic disruption losses will be significantly larger, it was assumed that the greater resilience of the region impacted by Sandy (as well as its probable greater ability to utilize tax credits) offsets much of this difference.

Disasters caused $186bn in damage

Disasters caused $186bn in damage